Storytelling is an ancient and time-tested pedagogy that has been used to teach and transmit knowledge for centuries. It is a powerful tool that can engage and captivate audiences of all ages, and it can be used to teach a wide range of topics, from history and culture to morality and ethics.

It has been an integral part of our lives since time immemorial. In Bharat, we have always had an oral tradition or Shruti based on Vedas which is passed on from person to person or teacher to student. Most of the Upanishads which are the nectar of Vedas are in the form of stories. Ramayana and Mahabharata in the form of History have taught us the way of thinking and way of living.

The essence of this research lies in the fact that storytelling is an intrinsic aspect of India’s educational heritage, deeply embedded in its culture and traditions. The objectives of the study are twofold: firstly, to critically analyze the historical significance of storytelling as a pedagogical medium in ancient India, and secondly, to assess its relevance and adaptability to address the challenges of modern education.

The study area encompasses a comprehensive examination of traditional pedagogical methods that employed storytelling across various ancient Indian educational institutions, such as gurukuls, tapovans, pathshalas and monasteries as a medium for knowledge dissemination, character development, and value inculcation.

The research methodology blends qualitative analysis with historical research. Primary sources including ancient texts, epics, and literary works will be thoroughly studied, analyzed, and interpreted considering their pedagogical significance in various contemporary subjects like, Mathematics, Language, Astronomy, Geography, Physics, Chemistry, Medicines, Technology, etc. to foster critical thinking, cultural preservation, and holistic learning.

Through this exploration, educators, policymakers, and scholars can gain insights into revitalizing educational practices, ensuring a harmonious blend of tradition and innovation.

Keywords

Communication, knowledge, learning, storytelling culture, subjective and objective views, spontaneous and pre-determined stories, reflective processing, cultural and emotional realities, reflective dialogue, and value-based learning.

1. Introduction

During the ancient period, once a Nawab of Rampur was ailing from a bout of bad cough and he could not speak at all. Local physicians (Vaidya) checked the Nawab and were unable to cure him. Multiple days passed by, and the Nawab’s situation worsened. Finally, the minister made an announcement in the kingdom and beyond that whoever cures the Nawab will be duly rewarded.

A wise physician called Liladhar came and said that he could cure the Nawab. He examined him and then asked the minister if he wanted to get Nawab cured by eating medicines or showing medicines. They were shocked and thought that Liladhar is arrogant. So, they asked him to cure the Nawab by showing medicines. Liladhar ordered 50 lemons and one knife to be given to him. Then he started cutting them in front of the Nawab’s mouth.

One by one after looking at them, water started coming out of Nawab’s mouth. The severe cough accumulated in his chest started dissolving and Nawab started talking. When Nawab saw the lemons one by one, rasa in form of juices started flowing out from his body. Similarly, stories are like those lemons which extracts the learning juices out of our mind and induces the learner to deeply connect with the subject and imbibe the learning.

2. Tradition of Storytelling in India

Storytelling has been an integral part of Indian culture for thousands of years, and it has played a significant role in conveying moral, spiritual, and historical lessons. Indian storytelling traditions are rich and diverse, encompassing various forms and mediums. Indian ancient literature is a vast treasure trove of wisdom that has been verbalized through narration of stories and passed on through generations, mainly via ‘oral tradition’ during the early phases. Storytelling in ancient India served an educational purpose, imparting moral values, ethical principles, and cultural norms. It was a way to educate and inspire individuals to lead virtuous lives.

Some key aspects of storytelling in ancient India

Itihasa or Epics: Two of the most famous and enduring Indian epics, the “Ramayana” and the “Mahabharata,” were traditionally transmitted through oral storytelling before being written down. These epics contain moral and ethical teachings and are still recited, retold, and adapted in various forms today.

Puranas: The Puranas are a vast genre of texts in which stories of gods, goddesses, heroes, and legendary figures are woven together with dharmic teachings and historical narratives. These texts played a crucial role in the dissemination of dharmic and cultural knowledge.

Jataka Tales: The Jataka tales are stories about the previous lives of Gautama Buddha, illustrating moral lessons and the path to enlightenment. These tales were widely used for teaching Buddhist principles.

Panchatantra: The Panchatantra is a collection of ancient Indian fables and moral stories attributed to the scholar Vishnu Sharma. It consists of stories that use animal characters to convey practical wisdom, moral values, and strategies for successful living.

Folklore and Regional Stories: India’s diverse regions and communities have their own unique storytelling traditions. Folktales, myths, and legends from different parts of the country reflect the cultural, linguistic, and geographical diversity of India.

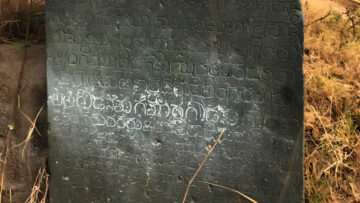

The Role of Visual Arts: Storytelling was not limited to oral traditions. Indian art, including sculpture, painting, and dance, often depicted stories from mythology and history. Temples and monuments served as visual narratives, with intricate carvings and murals conveying stories and teachings.

Sanskrit Drama: Sanskrit drama, particularly during the classical period, was a prominent form of storytelling. Plays like Kalidasa’s “Shakuntala” portrayed intricate plots, complex characters, and moral dilemmas.

In summary, stories were used to cultivate moral values, preserve cultural traditions, entertain people of all ages and develop character.

3. Literature Review on Ancient Indian pedagogy

There is some evidence to suggest that ancient Indian pedagogy had a positive impact on students’ learning. Research Studies Examples to support are summarized here.

National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) in India.

Title: A Study of the Comparative Effectiveness of Traditional Indian and Western Methods of Teaching on Academic Achievement and Creativity of Students

Authors: National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT)

Publication: Indian Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Apr. 2010), pp. 139-152

Result: Students who were taught using traditional Indian methods outperformed the students who were taught using Western methods on both measures of academic achievement and creativity.

The study compared the academic achievement and creativity of students who were taught using traditional Indian methods to students who were taught using Western methods.

a) The traditional Indian methods used in the study included:

Gurukula: A traditional Indian approach to education that emphasizes holistic development, including intellectual, physical, social, and spiritual development. Students in Gurukulas live with their teachers and learn through a variety of methods, including traditional Vedic chanting, memorization of sacred texts, and practical training.

Shloka recitation: The recitation of Sanskrit verses from ancient Indian texts.

Abacus training: A traditional method of arithmetic calculation using beads on a frame.

Yoga and meditation: Practices that promote physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

b) The Western methods used in the study included:

Lecture-based instruction: A traditional teaching method in which the teacher delivers information to the students in a lecture format.

Text-based instruction: A teaching method in which the students learn from textbooks and other written materials.

Drill-and-practice exercises: A teaching method in which the students repeat exercises until they have mastered a particular skill.

A study by the University of California, Berkeley

Publication: Journal “Educational Psychology” in 2013

Result: Students who were taught using a combination of traditional Indian and Western methods performed better on standardized tests than students who were taught using either method alone.

Source:https://csaa.wested.org/spotlight/culturally-responsive-instruction-for-native-american-students/

It was conducted on a group of 100 Indian American students who were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a group that was taught using a traditional Indian method, a group that was taught using a traditional Western method, and a group that was taught using a combination of the two methods.

The study found that the students in the combination group scored significantly higher on the mathematics achievement test than the students in the other two groups. The study also found that the combination group students were more likely to enjoy learning math and get motivated to succeed in math.

The study’s authors concluded that a combination of traditional Indian and Western educational methods may be an effective way to instruct Indian American students.

A study by the University of Chicago

Title: The Gurukula Method: A Traditional Indian Approach to Education

Authors: Freeman, Frank N.; Burks, Barbara S.

Publication: Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Feb. 1927), pp. 81-96

Result: Students who were taught using a traditional Indian method called “Gurukula” were more likely to attend college and to graduate with high honors than students who were taught using traditional American methods. The study also found that the Gurukula students scored higher on standardized tests of intelligence and achievement. The Gurukula method is a traditional Indian approach to education that emphasizes holistic development, including intellectual, physical, social, and spiritual development.

The authors compared the academic performance of two groups of students: one group that was taught using the traditional Indian Gurukula method and the other group that was taught using traditional American methods.

These studies suggest that ancient pedagogy can be beneficial for students in a variety of ways. For example, ancient Indian pedagogy is often characterized by a focus on individualized attention, experiential learning, and the use of stories and parables to teach moral values.

These approaches can help students to learn more effectively and to develop a deeper understanding of the material.

In addition to the studies cited above, there is also a growing body of research that suggests that ancient pedagogy can be beneficial for students in a variety of other ways, such as:

- Promoting social-emotional learning and well-being

- Developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- Fostering creativity and innovation

- Encouraging cultural awareness and understanding

Overall, the evidence suggests that ancient pedagogy has the potential to be a valuable tool for educators who are looking to create more holistic and effective learning environments for their students.

- Academic achievement: Students in the traditional Indian group scored higher on standardized tests of mathematics, science, and language arts.

- Creativity: Students in the traditional Indian group scored higher on tests of creativity, such as the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking.

The study also found that students in the traditional Indian group were more likely to report feeling satisfied with their education and to have positive attitudes towards learning.

4. Storytelling Elements

All the ancient stories followed a structure and used storytelling elements that created a compelling and engaging narrative for the listeners and readers, and they have etched in our memories for centuries.

(Figure 1: 5 S Key Story Elements with Example)

Our Ancients Aced the Art and Science (of Storytelling with) 5 Ss – Story Plot, Story Lead, Setting, Struggle and the Substance. These five key elements that form, what we call a ‘Story’, are explained here.2

Story-Plot: One of the most common storytelling elements used in ancient Indian literature is the plot. The plot is the sequence of events that happens in a story. It is what drives the story forward and keeps the reader engaged. Indian ancient literature often uses complex and intricate plots that span generations. For example, the plot of the Bhagavad-Gita, where in the Pandavas and Kauravas were engaged in a fierce battle and before the start of the actual war, Arjun had a nervous breakdown and decided not to fight. So, the celestial song of Bhagavad Gita which is a perennial philosophy was sung amidst the battlefield.

Story-Lead: Another important storytelling element is the character. The characters are the people or creatures who populate the story world. They are the ones who experience the plot and drive the story forward. Indian ancient literature often has large casts of characters, each with their own unique personality and backstory. For example, the Mahabharata has over 100 powerful characters, each with their own unique role in the story. These characters have different shades(black and white) and go through different conflicts. Maharishi Ved Vyas has portrayed the good side of Karna and few dark aspects of Pandavas, both in the form of stories.

Setting: The setting is another important storytelling element used in Indian ancient literature. The setting is the date, time and location where the story takes place. In Itihasa, it is mostly a real place. Indian ancient literature often uses vivid and detailed settings to create a sense of immersion for the listener or the reader. The setting of the Shrimad Bhagavata Purana is described in its narrative, which is primarily divided into twelve books or cantos (Skandhas). The setting varies throughout the narrative as it covers various stories and time periods.

(A) Setting at the Beginning

The Bhagavata Purana begins with a conversation between the sage Ugrashrava Sauti (Suta Goswami), and a group of sages gathered in the Naimisha Forest (Naimisharanya). The setting here is a sylvan, forested area where sages often assembled for spiritual discussions.

(B) Progressive shift in setting

As the narrative progresses, it shifts between different settings and time periods. It recounts the creation of the universe, various cosmic events, and the lives of several divine beings and avatars, including Lord Vishnu and Lord Krishna. These stories often take place in celestial realms, ancient kingdoms, and also the pastoral lands of Vrindavan, Mathura etc.

Struggle: This is another essential storytelling element used in ancient Indian literature. The struggle is the conflict or obstacle that the characters face in the story. It is what creates suspense and keeps the reader interested in finding out what happens next. Indian ancient literature often uses complex and nuanced conflicts to explore complex human emotions. For example, the central conflict of the Mahabharata is the war between the Pandavas who are trying to abide dharma (righteousness) and the Kauravas who follow the pursuit of pleasure often while following adharma (unrighteousness). However, the story also explores other conflicts, such as the conflict between two dharmas. Arjun faced the dilemma to follow the Kshatriya dharma or the Shishya dharma.

Substance: This important storytelling element is the central message or theme of the story. It is what the story is trying to convey about life, the world, or the human condition. Indian ancient literature often explores complex and universal themes, such as the nature of good and evil, the importance of righteousness, and the power of love. For example, the theme of the Ramayana is the importance of moral values and upholding dharma (righteousness). The story shows that those who follow dharma will ultimately be victorious, even if they face many challenges along the way.

The storytelling process often starts with a basic setting where the main character, the protagonist, is often faced with a problem. The protagonist then tries to overcome the problem with righteous intention and is usually victorious at the end. These five steps make it effective to convey complex information, moral lessons, and practical wisdom. They make abstract concepts more relatable and easier to understand, which is especially important for imbibing moral values and imparting life skills.

Let’s embark on a discovery journey to deep dive into various story elements of our ancient texts.

Upanishads

Let’s begin with Upanishads which is the nectar of Vedas. Upanishads are a profound record of the deepest spiritual experiences of the Rishis who by the power of their tapas could attain to higher realms of consciousness and realize many aspects of the Supreme Truth. Sri Aurobindo, the Rishi of India’s Renaissance, observed that the “Upanishads are documents of revelatory and intuitive philosophy of an inexhaustible light, power and largeness and, whether written in verse or in cadenced prose, spiritual poems of an absolute, an unfailing inspiration inevitable in phrase, wonderful in rhythm and expression.” The contents of the Upanishads are presented in the form of conversation between the Guru and Shishya/s and are often presented in the form of stories.

The beautiful steps of realization and the unveiling of the Panch-Kosha comes in the story of Bhrigu in Bhrigu Valli in Taittiriya Upanishad.

Story-Plot: The Upanishad begins with Bhrigu approaching his father, Varuna, and expressing a desire to know the ultimate reality (Brahman). He asks his father to impart that knowledge to him. Bhrigu approached his father and said, “Lord, teach me the Eternal.”

Varuna doesn’t immediately provide answers to Bhrigu’s questions. Instead, he instructs his son to inquire into the nature of reality through self-reflection and meditation. He encourages Bhrigu to look within and discover the truth for himself and asks him to seek the Eternal by tapas or concentration and meditation.

Story-Lead: Bhrigu and Varuna

Setting:Varuna, having explained this to his son Bhrigu, told him to seek the Eternal by tapas

तंहोवाच।तपसाब्रह्मविजिज्ञासस्व।तपोब्रह्मेति॥३॥

Taṃ hovāca | tapasā brahma vijijñāsasva | tapo brahmeti || 3 ||

(To him said (Varuṇa): By devotion, Brahman seek thou to know. Devotion is Brahman || 3 ||)

He also explained that the Eternal is that from which these creatures are born, by which they live, and to which they depart and enter again.

Struggle: Bhrigu followed the path and initially reflected that it’s Food (Anna) that is the true nature. However, on further reflection and Tapas, he thought that it’s Prana. Later, he realized that it’s the Mind (Man) and then the Intellect (Vigyan) is the ultimate form of reality. In his struggle, he progressed and realized that it’s not Anna, Prana, Man nor Vigyan that is the true form of eternal.

Substance: The Taittiriya Upanishad provides teachings and meditative practices to help individuals understand these layers and ultimately realize their true nature, which is the Atman or the eternal self. Through the journey with Tapas, he finally realized the true form of Ananda, real bliss. So, in the Panchkosha, one progresses and transcends one layer to another to realize the ultimate nature of reality.

Ramayana

Now, let’s understand the application of these story elements in Ramayana. In the Baal Kand, Rishi Vishvamitra comes to Ayodhya and takes Ram and Lakshman with him for 30+ days and travels to different places before finally reaching Mithila where Ram gets married. During these days, most of the conversations between Vishvamitra and Ram/Lakshman have been in the form of stories. History, Geography, Astronomy and the science of weaponry (Bala and Atibala Vidhya) were taught through various stories like the advent of Ganga, Samudra Manthan, history of Magad and Mithila, Gautam Rishi and Ahalya etc. All these are mentioned in Bal Kand of Valmiki Ramayana.

Story-Plot: Vishvamitra comes to take Ram Lakshman with him for 30+ days in the pretext of protecting Yagna. It turned out to be a continuation of education for Ram and Lakshman.

Story-Lead: Rishi Vishvamitra, Ram and Lakshman

Setting: In Baal Kand post completion of Tapovan education of Ram and Lakshman by Rishi Vasistha

Struggle and Substance: Multiple conflicts came in different stories of the advent of Ganga, story of Mithila, liberation of Ahilya, Samudra Mathan etc. and had associated themes with them.

Panchatantra

Let us take another powerful illustration of our ancient text – The Panchatantra.

There was a king called Amarshakti who ruled a kingdom, whose capital was a city called Mahilaropya. The king had three sons named Bahushakti, Ugrashakti and Anantashakti. Though the king himself was both a scholar and a powerful ruler, all of his sons were dull and stupid. The king despaired of his three princes’ inability to learn and approached his ministers for counsel. They presented him with conflicting advice, but the words of one, called Sumati, rang true to the king.

He said that the sciences, politics, and diplomacy were limitless disciplines that took a lifetime to master formally. Instead of teaching the princes scriptures and texts, they should somehow be taught the wisdom inherent in them, and the aged scholar Vishnu Sharma was the man to do it.

Vishnu Sharma was invited to the court, who knew that he could never instruct these three students through conventional means. He had to employ a less orthodox way, and that was to employ the pedagogy of a story through a succession of animal fables – one weaving into another – that imparted to them the wisdom they required to succeed their father.

Adapting stories that had been told for thousands of years in India, Panchatantra was composed into an entertaining five-part work to communicate the essence of diplomacy, relationships, politics, and administration to the princes.

These five discourses — titled The Loss of Friends – Sanskrit: “Mitra-Bhedaḥ” (मित्रभेदः), The Winning of Friends – Sanskrit: “Mitra-Laabhah” (मित्रलाभः), Of Crows and Owls – Sanskrit: “Kākōlūkīyam” (काकोलूकीयम्), Loss of Gains – Sanskrit: “Labdhapraṇāśam” (लब्धप्रणाशम्) and Imprudence – Sanskrit: “Pramattakumaaraḥ” (प्रमत्तकुमारः) — became the Panchatantra, meaning the five (pancha) treatises (tantra).

The names which he used for the animal characters and human beings are also interesting. Most of the time they either describe the physical appearance of the character or the other psychological attribute.

For example, in the fourth strategy Labdhapraṇāśam (लब्धप्रणाशम्), the name of the monkey is ‘Raktamukh’. Rakta literally means blood (here it means red), mukh means face, so the meaning becomes ‘one with red face or mouth’. In India there are red-faced monkeys.

We can take another example for the psychological attributes. In the first strategy, Mitrabhedah, there is a story of three fishes. The names of the fishes are Anagatvidhata (one whose destiny is undecided), Pratyuttpannamati (one who works using his intellect according to the situation) and third is Yadbhavishya (one who leaves everything on the destiny and do not work). So, he used appropriate names of the characters and used them in his teaching.

In this manner, Acharya Vishnu Sharma told 72 stories to the princes for six months. A story tends to have more depth than a simple example. These stories engaged the thinking and emotions of the princes and led to the creation of mental imagery.

Let’s explore one of the major stories from the Panchatantra, an ancient Indian collection of fables, using the five story elements.

Story: The Monkey and the Crocodile (वानरःमकरश्च)

Story-Plot: In a lush forest by a river, an unlikely friendship blooms between Raktamukha, the clever monkey, and Karalamukha, the cunning crocodile. As trust deepens, Raktamukha shares his sweet fruits.

Story-Lead: Raktamukha, a quick-witted monkey, takes the role of the protagonist, while Karalamukha, a scheming crocodile living in the same river, becomes the antagonist.

Setting: The story unfolds in a vibrant forest near a river, where Raktamukha resides in a massive tree on the riverbank.

Struggle: Tensions arise when Karalamukha’s wife craves the fruits. Caught between loyalty to Raktamukha and his wife’s demands, Karalamukha devises a cunning plan to deceive the monkey.

Substance

Raktamukha outsmarts Karalamukha by sending him on a wild errand to fetch his “heart” from the tree. This clever ruse mends their friendship but with a newfound caution. The story imparts lessons on trust, deception, and the enduring value of loyalty.

5. Science behind Storytelling

The most famous Plato quote on storytelling is: “Those who tell stories rule society.”

There have been great societies that did not use wheels, but there has been no society that did not tell stories. Story transforms us. Power of storytelling is even emphasized by Maharishi Ved Vyasa at the beginning of Mahabharata, where he says, “If you listen carefully. At the end you will be transformed and be someone else”. So, stories have a tremendous capacity to change our lives. They have the innate ability to change the way we see or perceive the world around us, the events that take place and shape our way of thinking and way of life.

Stories synchronize the listener’s brain with the teller’s brain. When the brain sees or hears a story, its neurons fire in the same pattern as the speaker’s brain. This is known as neural coupling. Entrepreneur and storyteller Leo Widrich wrote in his essay “The Science of Storytelling: What Listening to a Story Does to Our Brains” says that there is evidence to suggest that when we hear a story, “not only are the language processing parts in our brain activated, but any other area in our brain that we would use when experiencing the events of the story are, too.”

(Figure 2: How Storytelling affects the brain (Science behind Storytelling))

The neuroscience behind storytelling is a fascinating field of study that explores how our brains process and respond to narratives. Our ancestors would have known this and so the Stories have been a fundamental part of human communication and understanding how they affect our brains can provide insights into why storytelling is such a powerful tool for conveying information, evoking emotions, and building connections. Here are some key aspects of the neuroscience of storytelling:

Engagement and Attention

The brain is naturally inclined to pay attention to stories. When we hear or read a compelling narrative, our brains release dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward. This engagement makes us more likely to focus on and remember the information presented in the story.

Emotional Resonance

Stories have the power to evoke strong emotional responses. When we connect with the characters and their experiences, our brains release oxytocin, a hormone associated with empathy and bonding. This emotional resonance helps us relate to the story and its themes.

Mirror Neurons

Mirror neurons are a type of brain cell that fires both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing the same action. They play a role in our ability to empathize with characters in a story, as they allow us to mentally simulate their experiences and emotions.

Memory and Retention

The brain tends to remember information presented in a narrative format better than dry facts or data. This is often referred to as the “storytelling advantage” in memory. The brain organizes information from stories into a coherent structure, making it easier to recall.

Cognitive Processing

Stories activate multiple areas of the brain, including those responsible for language processing, sensory perception, and motor control. This widespread activation suggests that storytelling engages various cognitive processes simultaneously, enhancing comprehension and retention.

Persuasion and Influence

Stories can be powerful tools for persuasion. When we are immersed in a story, our critical thinking faculties may be temporarily suspended, making us more receptive to the messages and values embedded within the narrative.

Neurochemical Responses

The brain responds to the tension and resolution present in stories. As the plot unfolds, the brain experiences changes in stress hormones like cortisol and the release of endorphins when conflicts are resolved.

Neuroplasticity

Exposure to new or challenging narratives can stimulate neural plasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize and adapt. This suggests that storytelling can be a tool for personal growth and learning.

Social Connection

Storytelling fosters social connections by creating shared experiences. When people discuss stories, they bond over their interpretations, which can lead to increased social cohesion.

In summary, storytelling engages various neurological processes that affect our emotions, attention, memory, and social connections. So, our Rishis, seers and sages made story as a potent means of communication and a tool for conveying complex ideas, conveying emotions, and building relationships.

(Figure 3: Representation of Brain)

Stories are 22 times more memorable than facts alone and that is why perhaps the most famous TEDX speakers in the world use only 25% facts in their presentations and the remaining 75% are stories. Similarly, our ancestors also used stories in our ancient literature.

Valmiki Ramayana consists of approximately 24,000 slokas and final version of Mahabharata composed by Maharishi Ved Vyas consists of more than 10,0000 slokas. In spite of so much data, the essence of both Ramayana and Mahabharata is known to most Indians as they have been transmitted not as data but in the form of stories. The modern research of neuroscience vindicates that our ancestors knew how our brain works and processes the story. In summary, below are the benefits of leveraging stories in Pedagogy.

(Figure 4: Benefits of Storytelling)

6. Techniques used for delivering Stories powerfully

In ancient Indian heritage, rhetoric was an important field of study known as “Vakrokti” or “Alankara Shastra.” Rhetoric in this context referred to the art and science of effective communication, particularly in the realm of poetry, literature, and discourse.

Rhetoric in ancient Indian heritage was not only about persuasive or ornate language but also about expressing profound philosophical and spiritual concepts in a beautiful and evocative manner. It played a crucial role in shaping classical Indian literature, poetry, and philosophical dialogues.

Let’s delve deeper into this and discover how they are reflected in our ancient Indian literature which made them memorable and engage through the ages in India’s Educational Heritage.

Here are some ways in which rhetoric is employed in storytelling pedagogy.

Ethos, Pathos and Logos

The Greek scholar Aristotle referred to three modes of persuasion – Ethos, Pathos and Logos. Ethos appeals to credibility and trustworthiness, Pathos appeals to emotions, and Logos appeals to logic and reason. Effective storytellers use a combination of these modes to engage their audience.

Ethos – In Sanskrit, the concept of ethos or ethical appeal can be represented by the term “Dharma” (धर्म). Dharma encompasses ethical principles, moral values, and righteous conduct.

Pathos – The idea of pathos or emotional appeal can be conveyed using the Sanskrit term “Bhava” (भाव). Bhava encompasses emotions, feelings, and sentiments. Different rasas (emotional states) were employed to engage and move the audience emotionally.

Logos – The concept of logos or logical appeal can be expressed using the Sanskrit term “Yukti” (युक्ति). Yukti represents reasoning, logic, and rationality.

Our ancestors expounded this beautifully to establish credibility in stories, evoke empathy in the audience, and present logical arguments within the narrative. Let’s decipher this with the epic text of Ramayana.

Ethos in Ramayana (Credibility and Character)

Ethos in the Ramayana can be observed through the character of Lord Rama. Rama is portrayed as the embodiment of virtue, righteousness, and dharma. His unwavering commitment to moral principles and his roots in the glorious heritage of Raghu and Dilip establishes his credibility and character as a sublime, noble and just individual. His actions and decisions throughout the epic reinforce his ethos. So, he didn’t break his vow or deterred from his words even during the crisis of his life. Similarly, Sita smelled something suspicious when Ravan, disguised as a Brahmin, came to her and asked for Food. However, she remembered that in the lineage of Raghu, no Brahmin should be turned down for Bhiksha. So, she stepped out of the Lakshman Rekha.

Similarly, in Mahabharata, Bhishma is known for his unwavering commitment to his vow of celibacy and loyalty to the throne, which establishes his credibility.

Pathos (Emotional Appeal)

Pathos is evident in the emotional depth and resonance of the Ramayana. For example, when Sita is kidnapped by Ravana, the anguish and despair felt by Ram and Lakshman elicit a strong emotional response from the audience. It is described that Ram was talking to trees and asking them if they have seen Sita.

Similarly, in Mahabharata, the inner conflict and moral dilemmas faced by Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra are depicted in the Bhagavad Gita and they evoke a profound emotional response. The tragic outcomes of the war, including the loss of loved ones, also elicit deep emotions.

Logos (Logical Appeal)

Logos is exemplified through the logical reasoning and strategic planning of the characters in the Ramayana. In Chitrakut, there was intense debate between Ram and Bharat on who should ascend to the throne of Ayodhya. It was so rational and logical that even great thinkers like Rishi Vasistha, Janak were left speechless and could not intervene from either side. The epic explores various ethical dilemmas and philosophical discussions that appeal to the audience’s sense of logic and reason.

Figurative Language: Our ancestors used rhetorical devices such as metaphors, similes, personification, and hyperbole to make storytelling more vivid and memorable. They help create mental images and emotional connections with the audience.

(Figure 5: Rhetoric in Storytelling – “Vakrokti” or “Alankara Shastra.”)

Metaphors: A metaphor is a figure of speech in which one thing is compared to another thing that is not similar in a literal sense. Metaphors can be used to create vivid imagery, to express complex ideas in a simple way, and to make writing more engaging.

Metaphors are often used in storytelling to create a deeper connection between the reader and the story. By comparing the characters and events in the story to things that are familiar to the reader, the author can help the reader to better understand and relate to the story.

We find many Metaphors in our ancient texts. Let’s understand how the Metaphor of Tree is used in the initial chapter of Mahabharata to depict Dharma and Adharma.

Dharma Vruksh compared to Yuddhistira: Lord Krishna is the root, Arjun is the stem, Bhim is the branch and Nakul, Sahdev as fruits.

Adhrama Vruksh compared to Duryodhana: Dhritrashtra as its root and Karna is the stem, Shakuni is the branch and Dushasan is the fruit.

Source:

दुर्योधनोमन्युमयोमहाद्रुमःस्कन्धःकर्णःशकुनिस्तस्यशाखाः।

दुःशासनःपुष्पफलेसमृद्धेमूलंराजाधृतराष्ट्रोऽमनीषी॥११०॥

युधिष्ठिरोधर्ममयोमहाद्रुमःस्कन्धोऽर्जुनोभीमसेनोऽस्यशाखाः।

माद्रीसुतौपुष्पफलेसमृद्धेमूलंकृष्णोब्रह्मचब्राह्मणाश्च॥१११॥

– First chapter of AnukramanikaParva within Aadhi Parva

Another example of Metaphor is of a human body compared to a chariot in Kathopanishad. (Third chapter-valli). This helps an individual to reflect and let the Atma be the driver of our life and not our senses.

आत्मानँरथितंविद्धिशरीरँरथमेवतु।बुद्धिंतुसारथिंविद्धिमनःप्रग्रहमेवच॥३॥

Atmānam̐ rathitaṃ viddhi śarīram̐ rathameva tu |

Buddhiṃ tu sārathiṃ viddhi manaḥ pragrahameva ca || 3 ||

“Know the atman as the lord of the chariot, the body as only the chariot, know also intelligence as the driver; know the minds as the reins.”

(Figure 6: Example of Analogy-Body of Chariot)

Repetition: Repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of sentences (anaphora) can emphasize key points and create a rhythmic and persuasive effect. Indian stories often use repetition to emphasize important ideas or to create a rhythm or flow.

In Shrimad Bhagavada Gita, the key central messages are repeated multiple times across different chapters to reinforce the learnings.

For Example – The importance of Karma yoga, which is the practice of performing actions without attachment to the results is repeated in varied ways in multiple chapters.

Rhetorical Questions: Rhetorical questions are asked not to elicit answers but to engage the audience’s thought processes. They can encourage reflection and draw attention to important ideas or issues or make a persuasive argument.

The Kenopanishad is one of the principal Upanishads, which are ancient Indian texts that explore the philosophy and spirituality of the Vedanta. While it primarily focuses on philosophical and metaphysical concepts, it also contains elements of rhetorical questioning. Here’s an example:

In Kenopanishad, there is a famous passage that begins with a series of rhetorical questions to provoke thought and contemplation about the ultimate reality or Brahman. It is found in Kenopanishad 1.1:

ओंकेनेषितंपततिप्रेषितंमनःकेनप्राणःप्रथमःप्रैतियुक्तः।

केनेषितांवाचमिमांवदन्तिचक्षुःश्रोत्रंकउदेवोयुनक्ति॥१॥

Oṃ keneṣitaṃ patati preṣitaṃ manaḥ kena prāṇaḥ prathamaḥ praiti yuktaḥ |

keneṣitāṃ vācamimāṃ vadanti cakṣuḥ śrotraṃ ka u devo yunakti || 1||

In this passage, the text asks a series of questions, such as “By whom is the mind directed in its thoughts? By whom is the vital breath (prana) compelled to function first? By whom is this speech impelled to speak? Who is the god that directs the eyes and ears?” These rhetorical questions encourage the reader or listener to contemplate the ultimate source of consciousness, life, speech, and perception, ultimately leading to the exploration of the concept of Brahman or the supreme reality.

In this way, the Kenopanishad, like other Upanishads, uses such rhetorical questioning to stimulate philosophical inquiry and guide individuals toward a deeper understanding of the nature of reality and the self.

Parallelism: Parallelism involves using similar grammatical structures or patterns in successive sentences or phrases. It can create symmetry and rhythm in storytelling, making it more aesthetically pleasing and impactful.

Example: In the Bhagavad Gita, a section of the Mahabharata, Lord Krishna imparts wisdom to Arjuna. One of the verses that illustrates parallelism is from Chapter 2, Verse 14:

सुखदुःखेसमेकृत्वालाभालाभौजयाजयौ।

ततोयुद्धाययुज्यस्वनैवंपापमवाप्स्यसि॥38॥

“Sukha-duhkhe same krutva Labhalabhau jayajayau.

Tato yuddhaya yujyasva Naivam papam avapsyasi.”

In this verse, Lord Krishna is advising Arjuna to maintain equanimity in the face of pleasure and pain, gain and loss, and victory and defeat. The parallel structure is evident in the repeated use of the pattern “sukha-duhkhe,” “labhalabhau,” and “jayajayau,” emphasizing the idea of maintaining balance and not being affected by external circumstances.

This use of parallelism in the Mahabharata’s teachings emphasizes the importance of maintaining mental and emotional equilibrium in the midst of life’s challenges and is a key theme throughout the epic.

Antithesis: Antithesis, a rhetorical device that involves the juxtaposition of contrasting ideas or words within a sentence or in close proximity, can be found in various parts of the Mahabharata.

Here’s an example: in the Mahabharata, there are several instances where antithesis is used to highlight the moral and ethical dilemmas faced by the characters. The constant battle between Devas and Asuras in multiple ancient Indian literature represents that antithesis of a group of people following a righteous path viz a viz those not following the same.

Another notable example can be found in the Bhagavad Gita, which is a part of the Mahabharata.

In Chapter 2, Verse 14, Lord Krishna presents an antithesis:

मात्रास्पर्शास्तुकौन्तेयशीतोष्णसुखदु:खदा: |

आगमापायिनोऽनित्यास्तांस्तितिक्षस्वभारत|| 14||

“Matrasparshas tu kaunteya Sitosna-sukha-duhkha-dah.

Agamapayino ‘nityas Tams titiksasva bharata.”

In this verse, Lord Krishna is instructing Arjuna to endure the fleeting experiences of pleasure and pain, heat and cold, and joy and sorrow, as they are temporary and impermanent. The antithesis is evident in the contrast between “sitosna” (heat and cold) and “sukha-duhkha” (joy and sorrow), emphasizing the idea that one should maintain equanimity in the face of such opposites.

This use of antithesis in the Mahabharata, especially in the Bhagavad Gita, serves to underscore the philosophical and moral teachings imparted to Arjuna by Lord Krishna, highlighting the importance of maintaining balance and detachment in the face of life’s dualities.

Irony and Satire: Irony and satire are rhetorical devices used to critique or comment on societal issues through humour or sarcasm. They can be employed to convey complex messages within a story.

In Panchatantra and Hitopadesha, animal characters are used to convey moral lessons through irony and satire. The tales often depicted human weaknesses, folly, and hypocrisy in a satirical manner. There were texts specifically dedicated to satire, such as the “Subhashita Ratna Bhandagara,” a collection of witty and satirical verses, and “Kadambari” by Bana Bhatt, which includes elements of satire and social commentary.

Kalidas composed Abhijnanasakuntalam. In this famous play, King Dushyanta forgets about Shakuntala due to a curse. The irony lies in the fact that Dushyanta, despite having fallen in love with Shakuntala and marrying her, forgets her after the curse is invoked. This situation results in dramatic and ironic consequences as Shakuntala is eventually reunited with him.

In Bhagavad Gita, we can see the satire in the first shloka of second chapter uttered by Lord Krishna.

श्रीभगवानुवाच|

कुतस्त्वाकश्मलमिदंविषमेसमुपस्थितम्|

अनार्यजुष्टमस्वर्ग्यमकीर्तिकरमर्जुन|| 2||

Shrī bhagavān uvācha.

“Kutastvā kaśhmalamidaṁ viṣhame samupasthitam.

Anārya-juṣhṭamaswargyam akīrti-karam arjuna.”

Lord Krishna asks Arjun how this delusion has overcome him in this hour of peril? It is not befitting an honorable person. It leads not to the higher abodes, but to disgrace.

Foreshadowing: This technique has also been used widely in ancient Indian literature. It is a powerful tool that can be used to enhance the reader’s experience and make the story more memorable. It is a literary device in which a writer hints at what is to come later in the story. It can be used to create suspense, build anticipation, or surprise the reader. Foreshadowing can be subtle or obvious, depending on the writer’s intent.

The Mahabharata is rich with instances of foreshadowing. For example, the birth of Duryodhana, the primary antagonist, is accompanied by various ill omens and dark signs, foreshadowing the calamities he will bring upon the Kuru dynasty. The dice game that leads to Draupadi’s humiliation is another instance of foreshadowing, as it sets the stage for the great Kurukshetra war.

Symbolism: This is a literary device in which a writer uses symbols to represent something else. Symbols can be objects, places, events, or even people. They can be used to add depth and meaning to a story, to create suspense, or to surprise the reader.

The concept of the “third eye” symbolizes inner knowledge, intuition, and spiritual insight. It is commonly associated with deities like Lord Shiva and represents the ability to see beyond the physical world.

Symbolism has also come due to utmost efforts and penance by someone in their life and associated with a story. For example – Bhisma took a big vow to not marry and will not have any sons and also will worship the king in the image of my father who ascended the Hastinapur throne. He never broke it in spite of Satyavati telling him on a few occasions, so it is known as Bhishma Pratigya.

In a similar way, in Valmiki Ramayana, King Bhagirath does penance for several years and finally Ganga descends to the earth. So, the name is Bhagirathi, and this effort is referred to as Bhagiratha Prayatna.

Imagery: Imagery is a powerful literary device used to create vivid mental pictures and evoke sensory experiences in the minds of readers or listeners. Ancient Indian literature, including epics, scriptures, and poetry, is rich in imagery that serves to enhance the storytelling and convey deeper meanings. Here are some examples of imagery in ancient Indian literature:

The Natya Shastra, an ancient Sanskrit text on performing arts, provides detailed imagery and descriptions of various aspects of dramatic performance, including the emotions expressed by actors, gestures (mudras), and stage design. This imagery is essential for understanding classical Indian theater.

The Bhagavad Gita uses metaphorical imagery to convey spiritual concepts. Let us look at the imagery of tortoise to convey the quality of Sthitpragna.

यदासंहरतेचायंकूर्मोऽङ्गानीवसर्वश: |

इन्द्रियाणीन्द्रियार्थेभ्यस्तस्यप्रज्ञाप्रतिष्ठिता|| 2.58||

yadā sanharate chāyaṁ kūrmo ’ṅgānīva sarvaśhaḥ

indriyāṇīndriyārthebhyas tasya prajñā pratiṣhṭhitā

One who can withdraw the senses from their objects, just as a tortoise withdraws its limbs into its shell, is established in divine wisdom.

Let us look at another imagery mentioned in the Gita.

वासांसिजीर्णानियथाविहायनवानिगृह्णातिनरोऽपराणि|

तथाशरीराणिविहायजीर्णान्यन्यानिसंयातिनवानिदेही|| 2.22||

vāsānsi jīrṇāni yathā vihāyanavāni gṛihṇāti naro ’parāṇi

tathā śharīrāṇi vihāya jīrṇānyanyāni sanyāti navāni dehī

As a person puts on new garments, giving up old ones, similarly, the soul accepts new material bodies, giving up the old and useless ones.

Exaggeration: Exaggeration, also known as hyperbole, is a rhetorical device used in storytelling and literature to emphasize or overstate certain aspects, often for dramatic effect or to make a point more vividly. In ancient Indian stories and texts, exaggeration can be found in various forms to convey moral, philosophical, or aesthetic ideas or to create a sense of wonder and excitement. While these exaggerations may not be taken literally, they contribute to the rich tapestry of storytelling in ancient Indian literature. Here are some examples:

Puranas

The Puranas, a genre of ancient Indian texts that contain myths, legends, and dharmic stories, often use exaggeration to describe the immense scale of cosmic events. For instance, they may describe gods and demons battling with weapons that can split mountains or narrate the vastness of the universe in cosmic measurements beyond human comprehension.

Ramayana

In the Ramayana, the golden city of Lanka is depicted as a magnificent and opulent kingdom beyond compare.

Jataka Tales

The Jataka Tales, which narrate the past lives of the Buddha, sometimes use exaggeration to emphasize moral lessons. In the story of “The Hungry Tigress,” the mother tigress is said to have been so emaciated that her eyes gleamed like two burning lamps, emphasizing her extreme hunger.

In summary, rhetoric in storytelling is the art of using persuasive techniques and language to engage, entertain, and influence an audience. Effective use of rhetoric enhances the impact of stories, making them more compelling and memorable.

After a deeper understanding of storytelling, let’s quickly look how stories have been leveraged to teach various subjects right from the ancient and medieval period to modern times.

7. Storytelling used as a pedagogical tool for teaching various subjects

Through the above Literature review, we deeply analyzed the ancient Indian scriptures through the five storytelling elements and also explored the various storytelling techniques leveraged by ancient literature. In the section below, we will further elaborate how the storytelling can be used to teach the various subjects.

Mathematics in Lilavati: Bhaskaracharya II (1114-1185), a great mathematician as well as a skillful astronomer has made immense contribution to the fields of arithmetic, algebra, trigonometry, calculus, and astronomy. Bhaskaracharya’s magnum opus, ‘Siddhanta Shiromani,’ is divided into four parts, ‘Lilavati’, ‘Bijaganita’, ‘Grahaganita’, and ‘Goladhyaya’. While ‘Lilavati’ deals with calculations, progressions, and permutations. ‘Bijaganita’ deals with algebra, ‘Grahaganita’ with planetology and ‘Goladhyaya’ with the study of the spheres.

Like almost all scientific and philosophical works written in Sanskrit, Leelavati is also composed in verse form so that pupils could memorise the rules without the need to refer to written texts. Lilavati uses beautiful examples in the form of small stories to explain the concepts.

Of a group of elephants, half and one third of the half went into a cave, one sixth and one seventh of one sixth was drinking water from a river. One eight and one ninth of one eighth were sporting in a pond full of lotuses. The lover king of the elephants was leading three female elephants; how many elephants were there in the flock?

Another example is of a traveler, engaged in a pilgrimage, gave half (1/2) his money at Prayaag; two-ninths (2/9) of the remainder at Kaashi (Benares); a quarter (1/4) of the residue in payment of taxes on the road; six-tenths (6/10) of what was left at Gaya; there remained sixty-three (63) Nishkas (gold coins) with which he returned home. Tell me the amount of his original stock of money, if you have learned the method of reduction of fractions of residues. So, it also fosters a way of life along with learning mathematics.

Astronomy: The eclipses are explained in early mythologies of India as a story of demon trying to eat up the Sun and the Moon. As the story goes, the gods were cursed by the sage Durvasa because Durvasa took affront to the elephant of Lord Indra and trampled on the sage’s gift of a garland.

In Hindu astrology, Rahu and Ketu are known as two invisible planets. They are enemies of the Sun and the Moon, who at certain times of the year (during conjunction or opposition) swallow the Sun or the Moon causing either a solar or a lunar eclipse. In later evolution of the myth, Rahu and Ketu are defined as the ascending and descending nodes of the ecliptic and equator. When the Sun and the Moon come together at these points, we get a solar eclipse at the ascending node and lunar eclipse at the descending node.

Chemistry: We remembered the structure of benzene through the story of August Kekulé, a nineteenth-century German chemist who claimed to have pictured the ring structure of benzene after dreaming of six snakes connected to each other by their tails and heads.

Physics: Similarly, Archimedes thought long and hard but could not find a method for proving that the crown was not solid gold. Soon after, he filled a bathtub and noticed that water spilled over the edge as he got in and he realized that the water displaced by his body was equal to the weight of his body. And we all came to know the law of buoyancy.

8. Modern research vindicates Storytelling

The idea that we all possess innate capacities for creative learning has advanced significantly in recent years thanks in large part to the reflective movement. One of these skills is storytelling, and when it is employed thoughtfully, reflectively, and formally, tremendous learning is possible. (Clandinin and Connelly, 1998; McDrury and Alterio, 2002; McEwan and Egan, 1995; Pendlebury, 1995; and Witherell and Nodding, 1991).

As mentioned in NEP 4.6, in all stages, experiential learning will be adopted, including hands-on learning, arts-integrated and sports-integrated education, storytelling-based pedagogy, among others, as standard pedagogy within each subject, and with explorations of relations among different subjects.

The importance of students using their own culturally created sense-making processes to make sense of their experiences is taken seriously by storytelling, making it an effective teaching and learning technique (Bishop and Glynn, 1999). Additionally, storytelling has the power to strengthen the bond between students’ acquisition of new knowledge and learning from others. Additionally, sharing and digesting tales in a reflective manner gives kids the chance to build real connections with their peers. It is a culturally situated, collaborative, and reflective learning and teaching tool. (Beatty, 2000; and Mulligan, 1993).

According to the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), listeners can identify themselves in stories. Stories engage students in science, says Goldbaum (2000), but not as spectators but as active participants. Campbell (1998) came to a similar conclusion, proposing that by using media-inspired stories in the classroom, teachers might persuade students to see physics as relevant to their lives rather than just a dry collection of facts.

Thinking of stories as facts wrapped in emotions, that is why science communicators looking for ways to help people make sense of science and care about science-related issues, have renewed their attention on the potential of storytelling as a tool when communicating about science. We now have ample evidence that storytelling can be a powerful way to nurture engagement with science [Dahlstrom, 2014 ] and that stories help people to understand, process and recall science-related information [ElShafie, 2018 ].

A 2018 study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that students who learned social studies concepts through stories were 20% more likely to be able to think critically about the material and make informed decisions than students who learned the concepts through traditional methods.

(Figure 7: Study at University of Pennsylvania on learning through Storytelling)

A longitudinal study conducted by McCabe and Peterson (1991) and published in Contemporary Educational Psychology demonstrated that students who learned through storytelling methods displayed better long-term learning outcomes and retention of information compared to those taught using non-narrative methods.

A study by Hegarty and Mayer (1999) in the Journal of Educational Psychology showed that storytelling enhanced information recall and transfer of knowledge when compared to traditional expository methods of teaching.

A study by Green, Brown, and Sardone (2019) published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology found that problem-solving abilities improved in students who were exposed to problems presented within a storytelling context. They found that storytelling can enhance critical thinking skills.

In addition to these studies, there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence from teachers and students alike who have experienced the benefits of storytelling in the classroom. For example, a 2020 survey of over 1,000 teachers found that 90% of teachers believe that storytelling is an effective way to teach their students.

In 2021, CBSE introduced storytelling as a pedagogical tool. Several state boards have included storytelling in classroom teaching to make the subjects more interesting and retain the attention of the students. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) has recently introduced audiobooks in the schools to encourage story-based syllabi from classes II to V.

The National Book Trust (NBT) also conducted workshops for MCD school teachers to emphasize the importance of storytelling in primary schooling, under which audiobooks based on short stories in Hindi from Panchatantra were included. Earlier this year, NCERT introduced ‘Jadui Pitara’ for students aged between three to eight years to bring in an element of joy in education. Joseph Emmanuel, director (Academics), CBSE, tells the Education Times, “Storytelling is an important form of art-integrated pedagogy that can be used by the teachers for an effective curriculum transaction. Through storytelling, students can be made to understand difficult academic subjects with real-life examples which will connect learning with life and strengthen their academic base for the higher classes.”

Vibha Singh, senior vice president, Municipal Corporation Teachers Association (MCTA), says, “The idea of introducing audiobooks in MCD schools is to assist the teachers present the subject better. Storytelling would be instrumental in making the classrooms vibrant to enhance the learning outcomes in the primary wing of government schools.

8. Leveraging Technology to use Storytelling

The future of storytelling holds exciting possibilities driven by technological advancements, changing audience preferences, and evolving storytelling formats. Here are some key areas that highlight the future scope of storytelling:

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR)

VR and AR technologies enable immersive storytelling experiences. In VR, audiences can step into the story’s world, while AR overlays digital elements onto the real world. These technologies will revolutionize gaming, education, and entertainment.

Interactive and Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Stories

Interactive storytelling, often seen in video games and interactive films, allows audiences to make choices that influence the story’s direction. This form of storytelling will continue to evolve, offering more complex branching narratives.

AI-Generated Stories

Artificial intelligence can analyse vast datasets of existing stories and generate new narratives. While this raises questions about creativity and originality, it can be used to create personalized content and assist storytellers in generating ideas.

Immersive Theatre and Live Experiences

Immersive theatre productions, escape rooms, and live experiences are becoming increasingly popular. These events blur the line between fiction and reality, allowing audiences to become active participants in the story.

Blockchain and NFTs in Storytelling

Blockchain technology and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are being used to tokenize and authenticate digital assets, including stories. This could change how creators monetize their work and ensure ownership rights.

Collaborative Storytelling

Online platforms and collaborative tools enable people from around the world to come together to co-create stories, fostering a sense of community and creativity.

The future of storytelling is likely to be a dynamic and evolving landscape, shaped by the convergence of technology, creativity, and audience engagement. Storytellers will need to adapt to these changes, embracing new tools and techniques while staying true to the timeless art of crafting meaningful narratives.

9. Recommendations

Based on the above review of literature and research carried out the authors recommend the below suggestions:

As we consider the implications of this research, it becomes clear that storytelling is not merely a subject of academic inquiry but a dynamic force that continues to shape our lives.

In closing, storytelling remains a timeless and potent means of conveying the human experience. It invites us to explore the depths of our imagination, to empathize with others, and to connect with the world in profound ways. As we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of storytelling, let us remain mindful of its enduring power to inform, inspire, and unite.

With this paper, we have embarked on a journey into the heart of storytelling in ancient Bharat, and the path forward is boundless, promising new narratives, new insights, and new horizons for generations to come to connect with their roots.

A) Pride and Inspiration

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

– A Psalm of Life, By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

A nation is built where there is will and spirit to live together and have unwavering faith in their sacred land, people, texts and thoughts. Through the study of ancient literature and storytelling, one can understand the footprints of our ancestors and how they have set up ideals for us to cultivate a sublime way of thinking and way of life. To imbibe this spirit and propagate pride of our forefathers, and of our glorious heritage and our nation, we need to understand their life and work and stories is the best medium to achieve this outcome.

Stories instruct, clarify, enlighten, and provide inspiration. They provide respite from routine and mental stimulation. Both teachers and students find them to be very motivating.

It is a skill that can be used to teach, learn, and connect with our roots. In this way, we will be able to connect our millennials, Gen X and Gen Z to their real roots and instill in them a sense of pride and Asmita.

B) Develop true Identity

Our ancient scripture, Upanishads say,

युवास्यात्साधुयुवाध्यायकःआशिष्ठोदृढिष्ठोबलिष्ठः॥

Yuvasyat Sadhu Yuvadhya-yaka. Aashishtho Dhradhishtho Balishtho.

Be youthful; be a good-mannered youth; be studious, courteous, determined, and strong. Each word of this hymn is of essence. Let us investigate it.

Yuvasyat – Be a youth in a real sense. Young age is inherently gifted with creative energy. Only those who have enthusiasm to do something new are truly youth.

Sadhuyuva– Be a good mannered and law-abiding person so that they don’t get lost on an evil path. This requires each youth to keep cultivating the following four virtues:

Adhyayakaḥ – Regular Study of good thoughts to help them keep away from unworthy thoughts.

Ashiṣṭho – Be courteous in thinking, conduct and speech and be respectful towards others.

Draḍhiṣṭho – Implementing the decision with a dogged determination.

Baliṣṭhaḥ – Be strong to be able to fulfil their duties and to struggle against evil.

All the above qualities can be cultivated powerfully through the stories. It will help the youths and everyone else to understand their identity and become a true youth rooted in his or her identity. Jijamata helped to cultivate an identity for Shivaji with the rich stories from Ramayana and Mahabharat from a very young age and so he was firmly rooted to his divine goal.

C) Character development

Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experiences of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, vision cleared, ambition inspired, and success achieved. — Helen Keller.

In our ancient Indian literature, character has been the central focus and not career. Character development is a lifelong process. However, it begins with an inspiration to develop the qualities. What is the best way to spark interest, motivation and connection other than a story? Right when we know the baby is in the mother’s womb, we use the power of stories to connect to the baby so the child will be inspired to imbibe these qualities from their role model and become like him or her. In fact, the very purpose of education is character building and stories are the best medium to achieve this outcome.

D) Development of Integrated personality

Storytelling is a powerful tool that can be used to enhance the various perspectives horizontally and provide the breadth and at the same time help to develop deep expertise and enhance the depth. It can help to build a T shaped personality. By adopting storytelling across breadth and depth, we can create a more connected, informed, and compassionate society with empathy to the core with in-depth expertise and experience. Another aspect is to become a truly integrated personality. I can be a first-class engineer or doctor but a second-class or third-class friend, fourth-class husband and fifth-class citizen. As men do not live by bread alone, it is important to cultivate the holistic personality to strive for and experience emotional, sentimental, aesthetic, intellectual, psychological and spiritual happiness over and above the sensual happiness thereby creating a truly integrated being. Stories are the best ways to create this vision and motivate us to strive towards this direction.

Summary of Mind map

(Note: The present paper is authored by Shri Fenal P. Shah along with his team members – Dr. Shruti Sinha, Gaurang Bhatt and Manisha Dhiman).

References

Aubert, Maxime, et al. (2014). Pleistocene cave art from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Nature 514.7521: 223-227.

Bishop, R and Glynn, T (1999) Culture counts: Changing power relations in Education. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Beatty, B. (2000) ‘Pursuing the paradox: Emotion and educational leadership.’ Paper presented to the New Zealand Educational Administration Society on the occasion of the First Inaugural NZEAS Visiting Scholar Program, November, New Zealand.

Clandinin, D and Connelly, F (1998) ‘Stories to live by: Narrative understandings of school reform.’ Curriculum Inquiry, 28(2): 149-164.

Campbell, P. (1998) Using stories to enrich the physics curriculum. Physics Education, 33(6), 356–359. Goldbaum, E. (2000) Grant to advance case study approach. University of Buffalo Reporter, 31(21), 1.

Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(Suppl 4), 13614–13620. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Gerald F. Brommer, (2010). Illustrated Elements of Art and Principles of Design, Crystal Productions

McCabe, A., & Peterson, C. (1991). Getting the Story: Parental Styles of Narrative Elicitation and Developing Narrative Skills. In A. McCabe, & C. Peterson (Eds.), Developing Narrative Structure (pp. 217-253). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

McDrury, J. and Alterio, M. G. (2001) ‘Achieving reflective learning using storytelling pathways.’ Innovations in Education and Training International, 38(1): 62-73.

McEwan, H and Egan, K (1995) Narrative in teaching, learning and research. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Mulligan, J. (1993) ‘Activating internal processes in experiential learning’, in D Boud, R Cohen and D Walker, (eds.) Using experience for learning. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English). Information available from: 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 USA, www.ntce.org.

Pendelbury, S. (1995) ‘Reason and story in wise practice’, in H. Mewan & K. Egan (eds.) Narrative in teaching, learning and research. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Shah, P., Mayer, R. E., & Hegarty, M. (1999). Graphs as aids to knowledge construction: Signaling techniques for guiding the process of graph comprehension. Journal of educational psychology, 91(4), 690.

Sara J ElShafie, (2018) Making Science Meaningful for Broad Audiences through Stories, Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 58, Issue 6, December 2018, Pages 1213–1223

Witherell, C and Nodding, M (eds) (1991) Stories lives tell: Narrative and dialogue in education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Books

Maharishi Valmiki 8thCentury B.C “Valmiki Ramayan”

Valmiki Ramayan Darshan based on discourses given by Param Pujaniya Pandurang Shastri Athavale and published by Satvichar Darshan

Vijigishu Jeevan Vadbased on discourses given by Param Pujaniya Pandurang Shastri Athavale and published by Satvichar Darshan

Yuvanbased on discourses given by Param Pujaniya Pandurang Shastri Athavale and published by Satvichar Darshan

Web Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhagavata_Purana

https://www.uou.ac.in/lecturenotes/science/MSCMT-19/lilavati.pdf

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/39/42/8285

https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/2/verse/14

https://asitis.com/2/14.html

https://upanishads.org.in/storiesLeelavati

https://desarrollodocente.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Alterio_M._2003.pdf

Feature Image Credit: quora.com

Conference on Pedagogy And Educational Heritage

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.